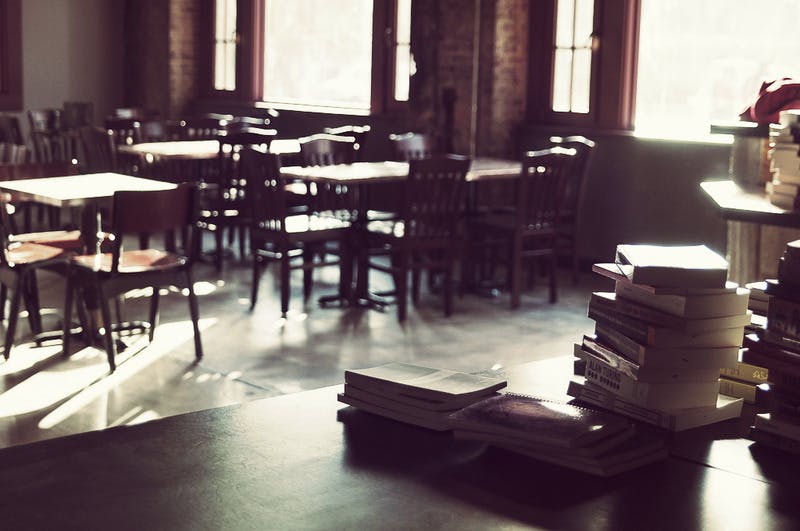

- Cafe

- Bookstore

- Upcoming events

- Book an event

- Catering

- Institutional and bulk sales

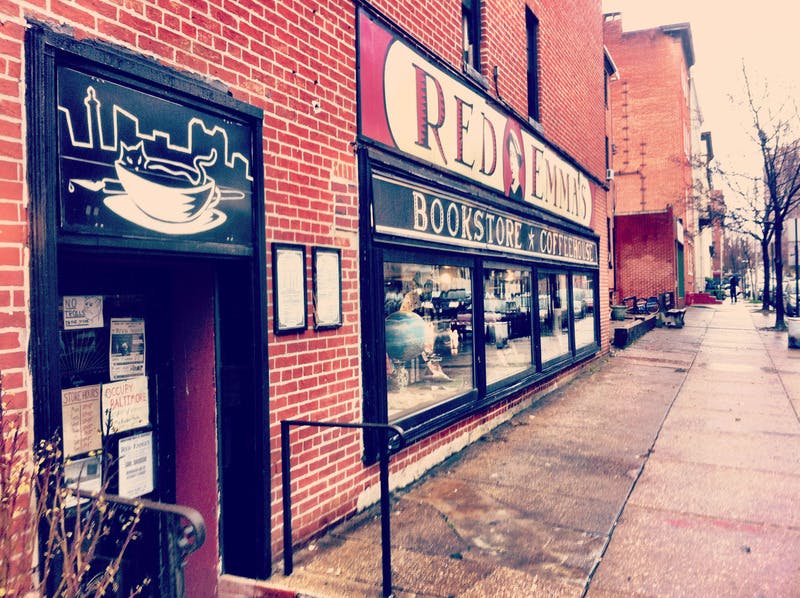

- About Red Emma's

- Press

- Buy gift cards

- Red Emma's merch

- Donate to the Red Emma's Education Fund

Our history

Our project started in 2004, rising from the ashes of Black Planet Books, a volunteer-run anarchist collective bookstore in Fells Point. In building a cafe component in the new space, we wanted to both establish a firmer financial foundation to keep the new project afloat, but also to create a more welcoming environment. There’s no point, after all, in a space dedicated to spreading radical information if the only people who ever come in are already radicalized!

Baltimore in 2004 was a very different place then it is today. When we started, radical, self-managed collective spaces were few and far between. While there were many amazing activists, radical artists, and politically engaged thinkers and writers in the city, there was no place to bring them together to spark encounters and conversations. If Baltimore today has a stronger network of social justice movements, and a rapidly proliferating movement of collectively run spaces and businesses, we’d like to think that our project has had some small part in making that happen.

Our mission is twofold: first, to demonstrate, concretely, that it’s possible to build institutions that directly put values like sustainability and democracy to work, and second, in doing so, to build a resource for movements for social justice here in Baltimore.

Radical?

At Red Emma’s, we’ve decided to call ourselves a “radical” project, rather than an “anarchist” or “communist” one. This doesn’t mean that we think anarchism and communism have nothing to offer as ways of thinking about what’s fundamentally wrong with the current world, and how to go about fixing it. But as a space that’s intended to welcome both people who have been in the struggle for decades and people just getting their feet wet for the first time, we felt that committing ourselves to a label and a specific ideological tradition was unnecessarily limiting. The people working on the project may be anarchists or communists, but the space is both and neither, or something else entirely.

“Radical” sums this up for us quite nicely; it’s a word derived from the Latin word for “root”, and to be “radical” is to go to the root of the problem, to not be afraid to attack root causes rather than be distracted by the symptoms on the surface. Being “radical” means that we’re always working to redevelop and reinforce our own political commitments, and to reach out to other people and communities who share our sense of outrage at injustice, but we’re not hamstringing ourselves in this work by insisting that every thing we do or every book we carry passes some dogmatic political litmus test.

Infoshops

Our immediate model and inspiration for our space is the “infoshop”: the DIY anarchist spaces that have started to spring up like mushrooms across the globe in the past few decades, building on long traditions of underground bookstores, hobohemian hangouts, and Utopian alternatives.

Practically, these kind of spaces arose to provide points of distribution for viewpoints and information that could never get a hearing in mainstream media and bookstores: not just books, but radical newspapers and periodicals, and self-published material like zines. In a world where information is treated like a commodity, an infoshop turns it back into something that belongs to a community. If an infoshop sells books and other merchandise, and even depends on these sales to keep the doors open, it’s never because of a desire to turn a profit: the mission is to distribute information you can’t find elsewhere, and to do so in a way which maximally agrees with the principles we’re preaching. Even as the internet has made getting access to radical information easier, the physical presence of an infoshop can help pop “filter bubbles”, exposing people to new ideas, and above all helps to bring people together to dream and scheme on how to turn information into a weapon in the fight for a better world.

Worker cooperatives

A big part of our project is demonstrating that the ideals we have politically are possible to translate into the real world. We want to show that anarchism doesn’t mean being disorganized and that anticapitalism doesn’t mean being unable to operate effectively and efficiently. If you’ve ever had to defend your conviction that the world would be a better place without bosses against hostile questions about who would take out the trash and who would scrub the toilets, you can point to Red Emma’s and win your argument. No bosses and no hierarchy, but we’ve been taking out the trash, ordering books, running a restaurant, dealing with the accounting, and a thousand other things for the better part of a decade.

Technically speaking, Red Emma’s is organized as a worker cooperative: everybody who is a part of the collective owns an equal share of the business, and has an equal voice in the decisions we make to run it. Worker cooperatives—which are taking off all around the country—are a way to build a world without bosses one workplace at a time, creating real world projects that meet the real needs of individuals and communities while at the same time staying true to the ideals of workplace democracy and an egalitarian division of wealth and labor.

Real Democracy

How do we make our decisions? How do you run a project that gets things done without having any one in charge? There’s a lot of different ways to do this; many cooperatives, especially larger ones, will use elected representatives in a way that’s similar to our ostensibly democratic system of government. At Red Emma’s, we try to take things a step farther; our decisions are made by consensus: we move forward with a decision only when everybody is in agreement (or at least when no one disagrees so strongly that they’d leave the project if a decision was taken).

Traditional forms of representation invite the concentration of power. Traditional voting encourages factionalization, and a competitive attitude towards making decisions, where the goal is to get your way by overpowering the minority. Consensus, on the other hand, is about treating people as valued equals, building the foundations of trust you need to take people seriously, to truly listen to what they have to say, and to work things out dialogically until arriving at a solution that everyone is comfortable with.

If we’re serious about our critique of power and power dynamics in the world around us, it’s imperative that we not reproduce these dynamics inside our own projects; consensus is a big step in this direction.

Proliferation of projects

Consensus decision making depends on two things: having a group small enough to meet face to face with everyone’s voice able to be heard, and having a group where everyone has a more or less equal stake in the decisions being discussed. As Red Emma’s has grown, we’ve tended to spin off new projects, rather than building a larger and potentially more hierarchical structure. To use a popular metaphor, we’ve expanded rhizomatically. Even our operations in our new, larger space has followed this logic: we've built a structure around empowering our departments (the bookstore and the cafe, for instance) to act as semi-autonomous mini-collectives within an overarching framework.

Our spin-offs have started off as projects of Red Emma’s proper, but have subsequently become independent collectives of their own. The first to do so was 2640, the community events venue we started in conjunction with St. John’s church in Charles Village. We found that our (then) small storefront wasn’t ideal for everything we wanted to organize, and we jumped at the chance to help save a historic building in partnership with a queer-friendly congregation committed to international solidarity and neighborhood activism. Today, 2640 is a vital resource for many Baltimore communities, hosting concerts, conferences, craft fairs, community dinner parties, fundraisers, lectures, films, and just about everything in between.

After starting 2640, we realized just how important it was to have autonomous spaces in Baltimore to support organizing work and non-commodified education. But 2640’s gigantic space didn’t make sense for small classes and workshops. That led to the birth of the Baltimore Free School, a community storefront school, where anyone can teach anything, to anyone, on a 100% free basis. In a world of commodified and stratifed education, we were excited to be putting forth an entirely different model, based in horizontal and noncapitalist social relations. We're excited that after a few moves to different spaces around town and a bit of a hiatus, the Free School will be joining us in the new location in Waverly.

These spin-offs are really just the tip of the iceberg; as a collective, we started and continue to run the Mid-Atlantic Radical Bookfair, now a part of the annual Baltimore Book Festival. We helped kickstart the annual Baltimore DIY Fest, worked as co-organizers of the City From Below conference and the STEW community fundraising dinners. And we’re starting new projects all the time...building off our collective infrastructure to build a better Baltimore.

Worker cooperatives are one particularly exciting area in which we've been able to help foster new projects, including Thread Coffee, which we incubated before helping launch it as an independent worker cooperative. We're a founding member of the Baltimore Roundtable for Economic Democracy, which has help support dozens of local worker cooperatives.

Our values

Being a worker-run collective is the foundation of our politics, but it’s not the whole story. Here’s some of the other commitments we put into practice on a daily basis:

- Sustainability: as far as is possible, we try to minimize waste, and maximize recycling and reuse.

- Animal friendly: we are a 100% vegan cafe.

- Safe space: there’s no room for racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, or ableist behavior in our space.

- Support for the independent publishing ecosystem: as much as possible, we support noncorporate presses and distributors that share our values.

Who is Emma?

Emma Goldman was born in 1869 in Lithuania, and emigrated to the United States at the age of 16. Four years later she had joined the anarchist movement, dedicating her life to the struggle against state tyranny, capitalist exploitation, and patriarchal oppression. Her fights against war and repression, for the rights of labor and for the rights of women to control their own lives and bodies—for which she was jailed, vilified, and ultimately deported—continue to inspire us even today.

“Red Emma,” as the mainstream press of the day called her, was by no means perfect. But she was always ready to reevaluate her own positions, making her one of the most open-minded thinkers of her time. Initially quite excited, like most revolutionaries, by the proletarian revolution in Russia in 1917, she was among the first international observers to condemn the bureaucratic authoritarianism which would smother the initial promise of the Soviet experiment.

Emma always understood that a revolution needed to be nurtured by revolutionary culture: her love of freedom in politics was matched by a love of experimentation in art, literature, and drama. We’ve named our project after Emma to pay tribute to her spirit of informed, creative, and multifaceted revolt.